Writing: Scene Choreography (2 of 3)

In Choreography Part I, we spent a considerable amount of time getting across the idea of parallelism, and how the serial (sequential) medium of writing attempts to simulate action in life. I used some fiction examples to show how internally experienced phenomena, along with externally observed events were interleaved together to create an active narrative. The idea of layers or “queues” was put forth to further illustrate the writer’s mechanism for deciding what elements to include or exclude when portraying a scene. With all that in mind, part two will pull back the focus a bit and study composition. What makes good scene choreography?

Let’s start off by recognizing that the word ‘good’ is subjective. For our purposes, let’s just agree to say that ‘good’ means ‘effective’ and ‘immersive’. If your reader gets involved and ‘feels’ the story, I think we can all agree that it’s a ‘good’ thing.

So, what we’re striving for is scene choreography that is easily visualized, and viscerally experienced. At this point I must caveat. Everything put forth here assumes that your reader cares about the characters, and about the story itself. If you haven’t done due diligence in drawing your characters and your world so that the reader feels something for them all the rest is just empty sound and fury. I can teach you movement and clarity until the cows come home, it is just wasted words without the character and setting foundation. So, having laid down that warning, let’s get to composition.

Composition in art is about balancing the elements, basically giving each element a “weight” and distributing things so that the picture has a particular “flow” or “pattern” that is deemed pleasing. One of things about good art is that there are contexts which draw the eyes to particular zones in the picture. This tends to be done with colors, textures and the overall layout of the work.

In writing, composition is very similar. It is structure. Many people are under the impression that fiction isn’t really constrained by structure. That is a fallacy. Like good art, fiction must have structure even if you don’t realize you’re imposing structure. I preach and preach and preach about effective transitions because they keep the reader oriented. In the literary world, and to beginning writers in school, a transition is merely a topic sentence. Pretty simple, huh? The difference is in fiction we can have topic sentences anywhere. However, they -strongly- gravitate toward the beginnings and endings of paragraphs and chapters. That’s structure– a pattern– and as we’ll see– patterns are good.

When I teach composition to students I break it down to it’s most simplistic core. When you write a paper, you tell us what we’re going to talk about, talk about it, then tell us what we talked about. For more advanced writers, it’s even more simple, it’s introduction, body, and conclusion. This really simple model scales from the entire breadth of a novel down to a single paragraph. This is what I call the writing atom, it is the fundamental binding structure that should and WILL hold ALL of your stories together.

At this point it may seem like a roundabout way to introduce scene composition, but a strong working understanding of the ‘bones’ so to speak makes the ‘whys’ of things a little easier to answer.

In movie production there is what is called an “establishing shot”. The establishing shot is usually a wide angle view of the scene setting. A good director may have an eye catch or something tertiary going on away from the main camera focus to draw your eye but not take away from the whole image. Then as things roll forward, there will either be a voice over, the camera itself will either focus down to the actual scene or there will be a cut to actual action in play.

In writing, your establishing shot is the introduction. In that introduction we set the scene and whatever events are in progress. As a whole, this introduction is a transition that leads-in or focuses the action down to the meat of the scene.

To continue our movie analogy, what follows the introduction are the “cuts”. Cuts are generally where there is a shift in the viewing camera. We are in the same scene but how we are viewing the scene is altered. We have close ups of characters, long shots, close shots, and so on. Directors do this for multiple reasons, to capture movement, to zoom in on emotions and reaction, and simply to keep the on-screen presentation interesting.

In written narrative, we generally don’t have cuts per se. Our most effective presentation is generally through one character’s eyes and just funneling all that input into the reader so it feels like they are in the story.

That is the significant difference between movie watching and reading a book or a story. Because a movie director has three mediums in their arsenal (visuals, characters, and music) their approach to story telling is multi-pronged. By this token, and the fact that they have visual and audible cues a director can seem to be in the heads of multiple characters at once without disrupting the flow of the story. What do I mean about audible cues? Music and sound foley. Characters and entities on screen can have tags. Who can forget Darth Vader’s theme music, or rumbling rise and fall in Jaws when the killer shark is lurking about. In the Terminator movies it was that pulsating rhythm accompanied the robot’s activities on screen. You hear the music and you’re set for what’s coming. For a director, the music and sound effects can serve as both transition and bridge.

Much of what we do in fiction is attempt to simulate some of these directorial short cuts. However, the best we can attempt to do is hope that the reader will imagine some breath-taking soundtrack to accompany whatever story we tell.

I will say that as you get more immersed and serious about your writing, imagining what music might be playing as the scene rolls will really dial you in to how you should be presenting the narrative. In movies, music and lighting set the mood and tone of the action. In writing, all you have is word choice and how things are experienced by the narrative viewpoint.

Let’s go back to scene cuts for a moment. I imagine its safe to say that if you’re reading this article that you are probably part of the ‘movie generation’ and have witnessed the evolution of movies and movie productions. I find that many writers, influenced by the way things are done on screen, try to emulate that in writing. It’s a good idea and what we essentially want to do, but what happens is that the visual artifice of camera shots gets confused with character viewpoint.

Let me emphasize here.

ONE VIEWPOINT PER SCENE.

I’ll reiterate in case I didn’t make it clear.

ONE VIEWPOINT PER SCENE.

I don’t care what you CAN do. I don’t care what you can make work or what the reader can follow.

ONE VIEWPOINT PER SCENE.

If I seem narrow, or you think you are misunderstanding me– you’re NOT. ONE– and ONE ==ONLY==. If it’s two or three, you might as well take TEN. If you divide the focus you divide the effectiveness– PERIOD.

Now, before you grab your marbles and tell me to kiss off because you like to jump around in characters let me be clear about what I am saying. PER SCENE, a scene meaning a single logical written “atom” that has a lead-in, body, and bridge. A large scene can consist of sub-scenes which simulate camera cuts in a movie, and we’ll get to that a little further on. It is permissible to do character and viewpoint switches between sub-scenes, as long as you don’t do it TOO MUCH. It’s a tool, and it can be effective when it’s employed for the proper reasons and emphasis. That said, your best bet is to switch viewpoints as LITTLE as possible.

Now, what ABOUT viewpoint? Sometimes I see writers who have this scatter-shot approach to writing. They describe the scene and we are hearing EVERYBODY’S thoughts, Dick’s thoughts, Jane’s thoughts, hell even the cat is going on tangents. Because things jump around, we never actually can focus on, or even figure out who is supposed to be the protagonist. Even if we can determine who the protagonist is, their own personal context is diluted by knowing what’s in everybody else’s head. To make matters worse, it becomes a battle of what the author tells us the character is thinking versus what they speculate other characters are thinking but the author has already told us… it’s just a MESS.

This is bad on so many levels, it tends to confuse the reader, it takes away mystery, and it dilutes the whole experience.

DO ==NOT== DO IT. Whatever you may be thinking, jumping around does NOT help your story. If your story works, it’s in SPITE of that technique, not because of it.

So, before I drop this single-viewpoint rant, just understand that the way you pull a reader into your story is by getting them to relate to your characters. You want them to walk in that character’s shoes, to feel and care about that person, and ultimately see the world the way that character does.

Now, tell me, when was the last time you walked into a room that wasn’t showing pornography that you knew everyone’s thoughts? Apologies to any psychics out there, but in the case of the rest of us, it’s a fair bet you haven’t and neither have your characters. Now, if you have a character who by some chance CAN read minds– okay– but the thoughts will be read and INTERPRETED by that character and THROUGH their viewpoint. The “head hopping” author is telling the thoughts as though from each individual character’s viewpoint not through a central focus.

Do yourself a favor– just don’t do it.

Now, the reason I’m on this rant is because in trying to do justice to a single viewpoint, we will go through some contortions that can at times be rather painful in their execution. The gains in reader identification are significant so it’s something we need to get over and live with.

So, we’ve beat the viewpoint horse to death and beyond, let’s get back on track, the actual scene composition or compositing. I took you through the thinking of the writing “atom”. It helps to think of writing “atoms” as being a self contained units. In a perfect world, each atom would be able to stand on its own independent of any other section of your writing. While this is not really feasible, it is a paradigm wherein the closer you come to achieving that independence the more universal that writing becomes.

In nature, compounds are constructed of elemental atoms, for instance, water is an oxygen molecule and two hydrogens. Scenes will be comprised of one or writing atoms. Very simple scenes may be a single atomic unit.

That “atomic structure” and your awareness of it is what will make larger aggregates of sub-scenes, and scenes form chapters, and clusters of chapters (sections).

For purposes of our choreographing chores, let’s correlate our written storytelling elements with movie and play elements:

- The stage or backdrop (setting)

- Music (mood / tags)

- Sound foley ( tone / environment / registers )

- Props (setting)

- Narrator / voiceover ( exposition )

- Actor (character)

As you can see, movie elements don’t really correlate that well. In order to simulate their effects we have to visualize and describe in such a way that the same effect is achieved in the reader’s mind. It seems like a great deal but as you’ll experience, it simply takes practice and thinking about scenes in a visual fashion.

Now, one of the things that I stressed in the earlier scene construction installments was the idea of chain reactions. When you choreograph a scene, chain reactions are your best friend. It is by considering the cause and effect of your scene elements that you can arrive at a dramatic portrayal.

In order for you to HAVE a chain reaction there has to be enough energy in the composition to give a definite direction or spin on events.

Take a for example, something fairly mundane. Our hero John has just lost his job, and he must go home to tell his wife and kids. We can have this happen in static no-friction environment OR we can inject energy into the situation… John comes trudging into the house to find a lavishly cooked dinner, stacks of groceries, and items from the department store that he knows they now can no longer afford. NOW, John has something react to. NOW, John has something to deal with. Because you’ve added explosive elements to the scene, the character is FORCED to react based on however you have developed them. Does John inexplicably explode in a rage? Does he start crying? Does he sigh, hitch up his pants, and brace to explain the bad news. If you’re one of those writers who really enjoys throwing rocks at their characters, then there’s a stack of bills on the table, and the landlady is on the doorstep tapping her toe.

The elements I’ve described (like the landlady) are what I call throw-away or catalytic elements. They are forces you introduce to stir up the character.

You can use these elements in volatile ways. Say the landlady totally gets in John’s face, and in frustrated anger he pushes her down the stairs. It’s an action (reaction) that has consequences. Those consequences force the character to react again.

When composing a scene, there should ALWAYS be sources of conflict and energy. Even calm romantic scenes should have a driving force if it’s a simple fear of rejection or the threat of being interrupted.

It’s critical when you look at a scene that you understand the energy in that scene. That energy or thrust of reaction is called the vector. In math and navigation, a vector is simply the path or direction that something is going. It is the same in writing. It is a “virtual” direction. For example, if John’s pushing the landlady down the stairs causes her to end up dead that event creates a decision point for John. If your general vector for John is to hit rock bottom, he can choose to cover up the death, or possibly call the hospital and be subject to the subsequent inquiry. In either event, the vector or energy is generally toward deeper consequences and higher stakes. A clear vector not only makes a scene easier to design and plan, but makes the scene tighter and more focused.

Let’s take that idea and apply it to a calm scene to see how it works.

Now, this is fairly lengthy segment, and the first few paragraphs are an internal monologue and description. While not much happens, the protagonist, Bannor, is tightly in focus the whole time. The setting details are focused through his eyes. Note, even here in this calm stretch there is a source of tension _Such miserable timing. He didn’t need more grief. Drawing a breath, he calmed himself._ External catalysts are pushing the character in the vector of the story’s main conflict.

One thing that you should note is throughout this passage Bannor is listing and detailing the conflicts in his life, including the trouble he will be in for slipping away to take a nap in the Queen’s private garden.

One of the reasons I picked this section is that when I planned it out, I knew it would be the only space where I would have the luxury of laying out the story situation. I wanted to present the particulars from a context where it seemed natural for the protagonist to be thinking about the complications currently making his life difficult. So what is the energy and vector here? While he’s trying to hide in the garden he has a incident (which I left out of the scene here for space considerations but is alluded to), in addition to that, his fiance shows up to chew his butt out for being a slacker. As a consequence, what would ordinarily be a flat expositive chunk of backstory is turned into a few moments in the life of our hero that helps us to understand him better.

Even the introduction of the woman he loves has a little edge to it as she stands over him a lets out an exasperated sigh. Another thing I’d like to point out is the protagonist describes his wife-to-be with his arm covering his eyes. Why? Because I could. Because it makes it different and more evocative.

Scene building and good choregraphing of the elements and setting relies not only on the energetic elements, but the way you present them. Even material where nothing happens can sustain if there’s a thread tying that information to the main plot and the vectors driving the scene and primary action.

Let’s do another scene, this time it’s a little more direct confrontation. When I put this together, I wanted something that was tense but at the same time had a “lighter” feel to it. In this, I wanted to establish some things about the protagonist, his character and who he is.

Now, things aren’t exactly exploding in this scene either. However, I’m pretty sure you can see, or at least SMELL that Og– right? Again this scene’s purpose is really to impart information to the reader about Corim without it being some expositive telling.

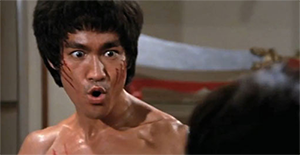

Look through this example and look at the motion and visual elements. There’s a lot of “motion” even when the characters are relatively static, hands clenching and unclenching, the way Corim shifts his boots to get a footing. There are also facial ticks and cues, as well as sounds and emphasis effects. All of these kinds of things are “action touches”. In a movie, it will be a quick camera cut to show a particular detail. In westerns it’s the cowboy pulling back the hammer on the gun, in martial arts they focus on the hands or feet preparing for action. They also do “eye shots” where the hero or villain narrows his or her eyes showing their determination. The action touches are a style thing, flourishes to emphasize what’s happening. Not every director or writer will handle these the same way, they are part of a “voice” that each of us as writers will develop as our skills increase.

In this installment on choreography we looked at structure, and idea of the writing atom. We also discussed the importance of chain reactions and energy vectors and how they focus and drive scenes. Lastly, we explored two fairly sedate scene examples and showed how arrangement, viewpoint and energy can keep the reader engaged. In the third installment of scene choreography we’ll get into the mechanics of scenes with more characters and more interaction.