Leaning back, you gaze up at the cloud dotted sky. The sun shines down brilliant and hot. For some reason, it seems brighter than at home. Your gaze is drawn to the lecturer as he ambles off into the trees. You get to your feet to keep him in sight a little longer. What was hidden in those trees? Since you arrived in this place there hadn’t been much opportunity to investigate. Then again, why should you need to? You came here to learn writing, not be an adventurer. You wouldn’t even worry about these things if it didn’t seem as though you were stuck in this unknown wilderness locale. That and you’re hungry. When would there be some food? You’d been through three classes already.

Running a hand through your hair, you glance to the other students. As they stand around whispering to one another you notice they’re more intense, more concerned now. Amongst the three-dozen people, conversing in several different languages it doesn’t seem that anyone knows any more than you do—and several seem more concerned. There must be something to this that nobody knows yet. Quite some effort had gone into bringing all these writers here and a bit more to provide the material for the talks. What point in doing all that to just strand everyone? Something didn’t add up.

There were still nine other classes left. That meant there would be plenty of time to consider the problem. Shaking your head, you study the trees where the instructor keeps hiding himself. Then again, perhaps a little extra research wouldn’t hurt. Learning more about this place that teaches writers might be valuable soon…

Writing: Narrative storytelling, the long and short

While the word ‘story’ is rather common, what it means to different people varies a great deal. Simply looking up the definition of the word will yield a number of differing meanings. According to Websters’ first definition, a story is ‘an account or a recital of an event or a series of events, either true or fictitious’. However, the ten subsequent entries list it anywhere from being a narrative, to being a lie or a romantic legend or tradition. In most of these variations, one finds that a story has something to do with events.

As writers, that’s the core of what story should mean to us. In the most general sense, a story is a chain of inter-related events. More concisely, it is a continuity. However, an event or continuity has no substance. They are merely ideas or concepts that have been experienced or imagined—it exists only inside the person who remembers them. It is the process of trying to share those mental pictures with others that most of us think of as a story. Actually, this retelling of memories is not a story but a narrative. A narrative is the medium by which a story is told. This distinction may seem fine, but the two things are quite different.

Creating a piece of art serves as a good analogy. An artist can depict a scene with several different mediums; with a pencil, with ink, with an airbrush, with pastels, acrylics, or oil paints. The artist can render the drawing with any of these tools, but each method has different traits and character. A pencil rendering is soft and uses only shades of gray to achieve the illusion of depth and perspective. An ink depiction has sharp edges, the blacks are solid and gradations of color must be handled with hatching or stippling. The other techniques use various kinds of color each with its strengths and weaknesses. Thus, the same recognizable picture can be portrayed in numerous ways, some of them more or less appealing to a particular observer.

When a writer tells a story, he or she has the same kind of choices as the artist. The difference is the medium. A writer uses words instead of various pigments. Also like the artist, the kind of story you’re trying to tell often influences the medium used. In the case of the writer, in devising your narrative you have several choices that are analogous to the decisions that an artist must make; the art surface, the kind of pigments, and the application tool (pencil, pen, brush, sprayer). As a writer, your art surface is the scope in which the story will be portrayed, whether as a short story, novella, novel or multi-volume saga. The artist chooses the surface based on properties like texture, absorbency, reflectiveness, and durability. For the writer, the choice of scope brings with it expectations and limitations that are like the properties of an artist’s surface choice. In a short story for instance, descriptions are by necessity briefer, the pace is quicker, and the realm of the premise is more confined.

The writer’s choice of narrative viewpoint, number of narrators and characters are analogous to the artist’s pigments and application tools. These choices affect the nature of how the story will be perceived by the reader.

Enough with theory and analogy, what about narrative technique? What will help you tell a story better? The background leading up to this is to help you realize the breadth of your choices and how they relate to story. Assume first that you know whether you’re writing a short piece or a long one. That in itself makes a lot of secondary decisions for you. The next choice is the viewpoint. Your choice will usually be a one of four or a variation thereof:

- First person — internal to one character only

- Third person limited — external to one character only

- Third person sectional — external to multiple characters by section

- Third person omniscient — external and prevalent to multiple characters

At the same time you choose a viewpoint there is a more subtle, but far reaching choice you should consciously make—that of tense. People from a journalistic background gravitate toward writing in the present tense. This kind of telling is more immediate, but carries with it a number of pitfalls and difficulties, the full scope of which we’ll save for another discussion. In short, present tense is problematic with editors and some readers. In short work, this choice is less of an issue. However, in longer fiction, it should be reserved to those with exceptional grammar and syntax skills.

Rather than try to argue the merits of one choice over another lets focus on what you as a writer are attempting to do. You are attempting to convey to a reader a movie as it plays out in your head. To you, the characters, situations, visuals and sensory are clear—or they should be. The task set before you is to take that entire multi-faceted experience and make your reader recreate it in their own head. When faced with the prospect of trying to evoke that entire vista of visuals and sensations most people balk and say it’s not possible.

It is possible.

It’s a matter of breaking a large problem down into the smaller pieces. When you consider your literary movie, think of it in terms of what kinds of information you must share with the reader. There are ten basic types of data:

- Visuals (what things look like)

- Environmental sensory (the sounds, smells, tastes, and feel of the place)

- Internal sensory (sensations a character experiences)

- Emotions (what a character is feeling)

- Thoughts (what a character is thinking)

- Dialogue (what characters are saying)

- Chronological orientation (transitions and the passage of time)

- Internal background (character history and synthesis)

- External background (world history and synthesis)

- Transitory synthesis (situational information [exposition])

If your narrative contains a balance of this information, you can communicate all the aspects of your story. If storytelling were like math, I might be able to describe a formula for effective narrative. Unfortunately, writing has little in common with math.

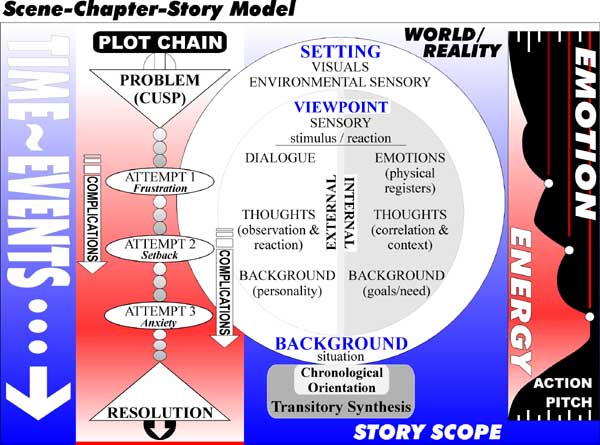

In the absence of a narrative formula, we can use a model to help us think about what we’re doing. The following diagram is designed to work across any scope of narrative, from the scene level all the way to thinking about an entire novel or series of novels.

At first look, this diagram might seem a little intimidating. It’s actually three depictions side-by-side.

At first look, this diagram might seem a little intimidating. It’s actually three depictions side-by-side.

On the left is the plot chain. The plot chain represents the structure of story, and shows catalysts that move the story forward.

In the center, is the representation of story elements. Outside the central circle are the world or reality and the story scope, those are the aspects of the narrative which enclose the main story elements. At the base of the story circle is the chronological orientation and the transitory synthesis that connect and run through the entirety of the elements. The outer circle consists of the setting and background that surrounds the story viewpoint. Inside the inner circle are the elements used to portray a protagonist’s point-of-view. The inner circle is divided in half showing the internal and external aspects of a viewpoint character’s interaction with the reader and the story.

The right side of the diagram is the graph of rising conflict or tension that should optimally prevail as the scene or story progresses toward its resolution. It is depicted here as emotion or energy. Some people are under the mistaken impression that this model is only for action stories. Conflict can take many forms and can be internal, emotional, or merely a frustration of the protagonist’s desires and objectives (the reconciliation with a loved one for instance). The key is for the narrative to build toward a critical turning point, and that the protagonist cares or has some stake in the events taking place. There is no right or minimum height or pitch for the energy at the climax. What is appropriate or “enough” is subjective. Usually your plotting is working as long as there at least some tension or energy building toward the turning point.

Using the model to create better narrative

For our purposes we’re going to work through writing a single short scene. First, we’ll determine the plot, and arrange the elements to create energy. Our short example will involve the hero reconciling with his girlfriend.

First we’ll set our action up on the plot chain:

PROBLEM: Our hero Sam in the bar and learns from his buddy that his girlfriend Jill no longer feels he cares for her, and is planning to leave. Startled, Sam throws back his chair and hurries to find his lady before it’s too late.

ATTEMPT 1: Sam goes to the inn where Jill is staying, and locates her. He tries to talk to her, but she walks away and several patrons at the inn prevent him from pursuing.

ATTEMPT 2: He tracks Jill to the stables, where she is saddling her horse to leave for parts unknown. We learn that if he lets Jill leave, he senses that she will be gone for good and he will never see her again. In this part, we have upped the stakes and urgency. Sam takes Jill’s hand and pleads with her. For a moment, she seems convinced. Spurred on by what seems a softening of her mood, he hurriedly goes on and accidentally mentions HER—the reason Jill wishes to leave him. With a roll of her eyes and a snort of disgust Jill pushes Sam away, jumps onto her horse and rides off.

ATTEMPT 3: Desperate to catch Jill, Sam steals a horse from the stable and pounds down the road after the receding love of his life. He catches up to her, trying to speak to her. His attempts at communication only anger her further and Jill cuts off the trail into the forest. Tears in his eyes, crying her name, he chases his love through the thick foliage. Vision impaired by his emotion, Sam fails to notice the low hanging branch in his path. With a yell of surprise and pain, Sam is unhorsed and crashes to the ground. Moaning weakly, he calls her name one last time as he hears the sound of her horse move off. He’s lost the only love of his life.

RESOLUTION: Lying on the ground, miserable and in pain Sam struggles to even focus. He continues to moan Jill’s name. After a moment, he blinks and realizes that Jill is standing over him with a concerned expression. Befuddled but knowing this is his last chance, Sam pours his heart out to her. Softened by seeing her beau injured and begging, Jill acquiesces and hugs him. She will give him another chance.

Note that in plotting this piece out, some of the emotion of the moment and words that might actually be in the story are included. This is a form of outlining that captures the essence of the story without going into detail. For purposes of this example, more detail than strictly necessary was used to illustrate building tension and an awareness of what’s at stake for the hero. These nuances are elements that you as the writer should already be aware of and therefore wouldn’t need to write them down.

From here, the narrative is built around the plot chain. The chain acts as the common thread throughout the scene. We open with an establishing shot—the camera (narrative) eye gives us a quick overview of where we are and who is present. This opening shot should include details from at least three senses like sights, smells, and sounds. The establishing shot is usually short (3 paragraphs max). After we’ve set the scene and introduced Sam, his friend and the seedy bar, we set up the problem. Sam and friend discuss a few things, and then his friend lets drop that Jill is going away. Here we need dialogue obviously, and when it is revealed that Jill is going away it’s critical that Sam react. He must have a physical and emotional response that SHOWS he cares, and that losing Jill is important.

After the revelation we need a transition. The transition should clue us we’re moving from the bar scene to the inn where Sam is going to brace Jill. This can be as simple as a space break, or a few lines describing his walk from the bar to the inn with Sam’s mind in a turmoil over what could have upset Jill so much.

The inn is a new setting and should be described. You don’t have to set each scene with an elaborate description, but it’s always good to keep the reader tuned in to where we are and what the place is like. This scene involves and focuses on Jill, so particular attention should be paid to her description, even if she’s been described before. In this case, it would be good to note her body language, the clipped sound of her voice, and the icy stare she gives Sam as he tries to talk to her. Again, because this bit is about the relationship between Sam and Jill, when she rebukes him, Sam must react—he must feel and dread what is happening. When the patrons at the inn tangle him up and keep him from stopping Jill, we must feel his frustration and be shown his concern. At the end of this bit, we must transition out of the inn. Again, we should make the reader aware that we’re changing locations.

Sam arrives at the stables and his second confrontation with Jill. By this point, the writing should take on a little greater urgency. The description of the new scene should be provided, but now Sam is in a different frame of mind and the details he picks out are different. His dialogue will be more clipped and more impassioned as he tries to talk Jill out of her anger. Attention would be paid to facial expressions, tone of voice, and body language. Jill might with stand hands on hips, or with her arms folded, head to the side and eyes narrowed. These are details which SHOW attitude and bring immediacy to the scene. Sam’s energy should rise in pitch as it appears he’s convinced Jill that everything okay, and then he should have a crushed and shocked feeling as he realized he’s gone and said something stupid. He needs to burn with frustration with himself as Jill leaps onto her horse and rides away. Through this scene we need to stress that if Sam fails, he will lose Jill forever and it will be a devastating loss. So, when Jill does ride off, we feel Sam’s desperation as he steals the horse and rides after her.

Scene setting and sensory are important in the chase scene, both in how Sam’s feelings are given and the mood and tone of the words used to describe the pursuit. Sentences will grow shorter, and more compact, and sensations more sharp and poignant. It’s important that Sam’s physical registers reflect his desperation—his thundering heart, his tight chest, the tears that burn on his face. At the crux, when he falls from the horse, his sense of defeat should be strong and painful, mingled with the emotional loss that is tied to the sound of her horse going further and further away.

The transition from apparent failure to success should be handled carefully. Even as Jill is looking down at Sam, the writer shouldn’t give away what will happen too quickly. Her expression should echo her incredulity, and even Sam should think right up to the last moment, that even this last ditch plea for mercy will be turned away. When Jill does give in, we should feel Sam’s explosive burst of happiness. We should feel the embrace he gives the love of his life, and see in her expression and words that it is true.

As described here, effective narrative is about analyzing the dramatic aspects of a scene. Attention should always be paid to specific feelings, sensations, expressions, and such that show the elements of the story without the author TELLING the reader. In any scene or situation you create, consider what the real focus will be. Use physical sensations to depict emotion. For example, a hot face for anger, or blurry vision and leaking eyes for sadness. Be aware of the stakes that your protagonist or viewpoint character has in the situation. Make sure they’re motivated and that the reader knows that motivation.

More about handling narrative and “showing” the story will be described in the next section where we’ll deal with seeing the difference between exposition and sensory narrative. We’ll also revisit the model and talk about some more of the aspects in detail. In the end, there’ll be examples of showing versus telling, and how to turn blocks of back-story and exposition into active narration.