Writing: Defining Narrative

By Will Greenway

From the Narrative Innovation Workshop warm-up lecture

Let’s start by posing a simple question. What does the word ‘narrative’ mean to you? I pose this question not just academically. It’s a fundamental question that a writer needs to be able to answer and fully understand. Many writers, even advanced ones don’t necessarily know the functional answer.

To be of most benefit to writers beginning and not, we should begin with what narrative is not.

- Description

- History / Facts / Research

- Opinions / Ideas / Prejudice

It seems overkill to put it up in lights like that, right? Certainly, once you lay those terms down it’s pretty obvious that those things are not narrative. If it’s so obvious, why is the most common beginner writing mistake to start with some long description about a place, or to detail some history about the story to come? Focus on that for a moment. The most common mistake is to start a story with material that isn’t narrative. Does that make sense? It shouldn’t. Yet, inexplicably it happens. Largely it’s because schools don’t teach creative writing. More, many teachers who have only written academically don’t understand fiction. Being able to write topic sentences and wiz-bang thesis statements does not a fiction writer make!

Now that we’ve introduced the problem, and explored the wrong answers. Let’s delve into the right answer. We’ll highlight it to drive it home:

- Events

- Viewpoint

- Temporal structure

At this point, some readers are going to be thinking that isn’t how they would define narrative— they were probably thinking something simpler. We’ll get to that. The simple answer is too simple. To write successful fiction it requires a little more insight.

For Want of a Nail

For want of a nail the shoe was lost.

For want of a shoe the horse was lost.

For want of a horse the rider was lost.

For want of a rider the message was lost.

For want of a message the battle was lost.

For want of a battle the kingdom was lost.

And all for the want of a horseshoe nail.

From the top, narrative contains events. This is another thing that may seem obvious. When we talk about events, we mean something happening. Not something random like a bear farting in the forest. An event that is tied to a sequence that culminates in a change (or a failure to change). These happenings relate to a character or characters and should have some manifest effect on their needs and desires (goals). When we talk about events, they don’t have to be bombs going off. They just need to have weight and mean something. The essence of this is captured in the simple statement “The kingdom was lost for want of a nail”. The missing nail is a trivial thing, but in the instance of the tale it has far-reaching consequence. So, to restate, a narrative contains events of significance that are tied to the destinies of the protagonists and the arc of their change.

After events, viewpoint is the center of narrative. By viewpoint, we mean character. The significant events are being related by or affect people in the frame of the narrative. That’s not to say that viewpoint can’t be the omniscient author/narrator, it can be. However, a reader is better engaged when the events are related as they are experienced by a character. This allows the reader to vicariously share the the protagonist’s senses and emotions. This is a critical element of suspension of disbelief, and is therefore the cornerstone of a strong involving narrative.

Last in our list is temporal structure. This is a more abstract concept but it is the foundation upon which the other two aspects sit. The narrative has to start someplace, and it has to end. That’s the narrative scope. From ancient times, when narratives were only about where food and shelter could be obtained, a narrative was only comprised of sequential time structure, beginning to end, events related as they happened. However, with the advent of more advanced narration techniques, the story could start with the end, then depict the events that led to that conclusion. (I personally have never liked those kinds of narratives, but it is seen frequently.) As you might have surmised, the temporal structure can contain flashbacks of course. It can also be how the narrative is told. Most structures are past tense, however, present tense is an option as well. All the details aside, time and how it is managed is a critical aspect of narrative. Whole novels can be framed around a few minutes of time or a single event.

We’ve burned up a bunch of words building a very specific model of narrative. So, what about the prevailing understanding of the definition? Many people believe (and will defend the position) that narrative is the same thing as story. They are not the same. At its foundation a narrative is simply the elements described above. Essentially, a narrative is just history, memories replayed for their informative value. As I stated earlier, the first narratives were simply where our ancient predecessors found food and shelter. The topic and structure were simple. It was retold by the hunter who experienced it (through verbal ques, gestures, and pictures scratched in the dirt), the events described in order with some sort of reference to how long ago they happened.

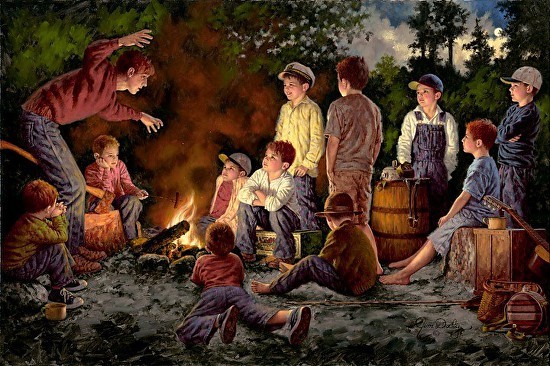

Where narratives were about subsistence, stories had a far different function; to entertain. When we speak of entertaining, we touch back to my specific redefinition of narrative: significant events told through a character in a fixed scope of time. When we focus on entertainment or enjoyment, the writer should consider the oral story-telling tradition. People sitting around a fire listening to events being retold for their emotional impact (excitement, humor, etc.). If you are verbally telling such a story, you have a limited amount of time to tell it—so therefore you omit anything that’s not significant or important to getting the desired effect.

If stories are entertaining narratives, how do we define “entertaining”? In general, we can interpret this to mean something pleasurable or interesting. Refer to the call-out below:

- About people

- Engaged by obstacles and/or adversity

- Featuring interesting / intriguing settings, concepts, or personalities

- Ultimately concluding in a way that satisfies the audience

This definition might seem confining and it is. You could say if your narrative fits the model, then your narrative is “safe” in terms of whether or not it meets the criteria of being a story. There are many examples of published works that do not meet all of the above criteria. I know this because I was forced to read them. However, I would challenge how “entertaining” these works were. Intellectual peculiarities, perhaps, but definitely not fun to read. Literature classes have forever made me suspicious whenever the word “classic” was tacked onto the front of something. It was usually attributed to something challenging like James Joyce’s Ulysses or Finnegans Wake.

In the interests of completeness let’s caveat the entertaining story definition:

- Subjective but agreeable.

- Opinions often diverge on what “entertains”.

- It’s easy to agree on what doesn’t entertain.

- Don’t abandon the model simply because existing published works don’t fit.

- Being published and being entertaining and/or successful are not the same!

The intent here is not confine your thinking. The intent is to help you integrate the very important concept of entertainment into your understanding of writing and publishing. If you don’t care if it’s published (or feel you live under a lucky star), by all means fly in the face of this advice. If you live in the same realm with me and want others to read your story focus on the critical pillars of entertaining narrative outlined here. Focus on the people of your story, on the events that affect their needs and desires, and ultimately concluding in an epiphany that will satisfy the reader. Stick to that and someone somewhere will enjoy it.